Alaskan food encompasses a wide range of traditions reflecting the diverse history of the 49th state. Roughly 20 percent of the state’s population identifies as Native Alaskan, which means Indigenous foodways are still a central part of life. Especially in the southern coastal regions, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Haida communities still preserve their ancestral traditions. Newer arrivals, such as prospectors during the Klondike Gold Rush, brought their own foods with them.

Alaskans from all different communities have relied heavily on what the land and the sea can provide, from foraged berries and hunted game, to wild-caught salmon, halibut, and king crab. Today, diners figuring out what to eat in Alaska are spoiled for choice. Food here is often seasonal by necessity and sustainable by design.

Here are some essential foods to try on your next adventure to Alaska.

Salmon

Salmon

For salmon-lovers, there’s no better place to feast than in Alaska. For Tlingit and Haida people, wild salmon has been a primary food source for centuries. Long before the arrival of European colonists, these coastal nations were trapping, curing, and roasting these prized fish. To this day, a few Native Alaskan smokehouses still adhere to traditional methods.

Because wild salmon has long been so central to life here, Alaskans are protective of this precious natural resource. Wild salmon populations here are carefully monitored in order to prevent overfishing. Unlike their farmed counterparts, these wild fish contain no antibiotics, colorants, or other additives.

There’s quite a bit of variation between the wild salmon species caught here. Chinook, Sockeye, Coho, Pink, and Keta are the five species of salmon that ply the waters of Alaska, and each has its own season and taste characteristics.

Salmon bake

Chinook, aka King Salmon, the largest of the salmon species, runs in season May through July. This variety’s bold flavor and luxurious texture make it perfect for grilling over open flame or charcoal, broiling, or baking.

Its high, healthy fat content ensures that it cooks up moist without losing flavor. You’ll find it on restaurant menus simply grilled, broiled, or baked, which enables the full flavor of the fish to be the main attraction.

From June through August in Alaska, sockeye salmon, with its deep bright red color and meaty, but not overpowering flavor, is found on restaurant menus grilled, broiled, or baked. It’s popular for smoking to be used in sandwiches, chowders, and dips.

Silver salmon

Coho or silver salmon runs in Alaska rivers July through September and are sought after by fishermen during the later part of the fishing season. Their red-orange flesh is more delicate and subtle in flavor than Sockeye or Chinook, which some say is the perfect balance.

Pink salmon is the smallest of the Pacific salmon varieties and easily caught with rod and reel. You won’t find these on restaurant menus since they are processed for canning and seafood products.

Alaska Salmon Bake, Fairbanks

Whichever variety of salmon is in season during your Alaska vacation, enjoy a fantastic feast at an all-you-can-eat salmon bake held in rustic lodges or picturesque outdoor venues.

At Ketchikan, “the salmon capital of the world,” watch schools of salmon at Ketchikan Creek as they make their way upstream, then order salmon simply grilled or smoked in a savory cornbread or a creamy chowder at one of Ketchikan’s restaurants.

Spot Prawns

Spot prawns

Fishermen often refer to Pandalus platyceros as “Alaskan lobster” for its impressive size. These prawns—the largest in the state—can be up to 10 inches long. Outside of Alaska, this delicacy is both rare and incredibly expensive.

Spot prawns boast incomparably sweet flesh that shines in all manner of preparations. They’re wonderful sautéed in butter, gently poached in an aromatic broth, or served raw. Alaskan fishermen also use responsible fishing methods to catch these coveted shellfish.

Halibut

Halibut

Mildly sweet, lean, and firm-fleshed, Pacific halibut, a member of the flounder family, is plentiful in all Alaska waters in the same May to September season as salmon.

Alaska’s fine dining chefs make the most of the fish’s mild flavor and firm texture, knowing how to keep this lean fish moist with dishes such as crab and macadamia nut stuffed halibut, oven-roasted halibut with butter sauce, and halibut sous vide in lemon olive oil.

At casual Alaska food trucks, bars, and eateries, you’ll find halibut burgers, thick filets grilled and served on a bun with the usual burger accompaniments; fish and chips-style, batter-fried pieces of the fish served with fries, tartar and cocktail sauces; halibut tacos and halibut enchiladas with salsa verde; and a Seward favorite called Bucket of Butt, chewy chicken nugget lookalikes served by the bucketful with tartar and cocktail sauces.

Rockfish

Rockfish

If you’ve never been to Alaska, there’s a good chance that you’ve never tried rockfish. Although abundant in Alaska, this prized catch can be tough to find elsewhere. That’s a shame, because rockfish is delicious, with a mild flavor and firm, but flaky texture reminiscent of cod.

Rockfish takes well to a number of preparations, including grilling, broiling, and searing. The one that you’re most likely to see on menus in Alaska, though, is fish and chips. Although Alaska hardly invented the British staple, it’s ubiquitous here—and often very good.

While in other places, fish and chips often winds up being made with cheaper whitefish like pollock, in Alaska, premium rockfish or halibut is often the go-to. With their meatier texture and exceptional flavor, these take the pub classic to another level.

Crab

Dungeness crab

For real seafood lovers, Alaskan crab, both King crab and Dungeness crab, is a not-to-be-missed delicacy made all the more special because of its seasonality.

Three species of King crab—red, blue, and brown (golden)—are each found in different Alaskan waters around the Bering Sea. These 10 legged crustaceans grow fat and meaty as they feed on the sea bottom.

Alaskan King crab

There’s nothing better than cracking into steamed and chilled claws and legs served simply on a bed of crushed ice fresh lemon wedges, or served steam-warmed with butter. Picking out the sweet, succulent crab meat is sometimes tricky, but is always a local meal to be savored and fondly remembered.

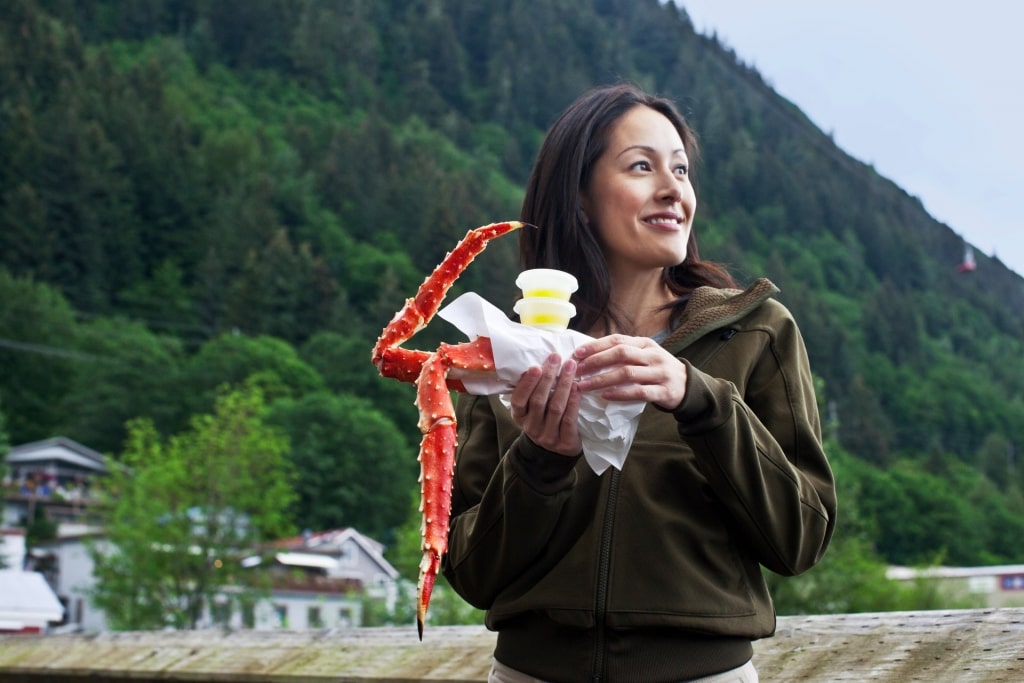

Tracy’s Crab Shack, Juneau

Some waterfront crab shacks serve specialties like crab cakes, crab chowder, open-faced crab sandwiches, and Crab Louie salad, as well as other fresh Alaskan seafood throughout the year.

Dungeness crabs tend to be meatier than other crab species, and they’re usually served steamed whole with drawn butter. Plan on early dining because they often sell out quickly.

Oysters

Oysters

Three kinds of Pacific oysters are cultivated in Alaska’s cold and pristine waters. Feeding off the plentiful amounts of plankton, they become fat and rich, with exactly the right balance of sweetness and brininess.

Hump Island oysters are a treat to try when visiting Ketchikan, as they’re cultivated in float trays made of local cedar submerged in the deep waters of the Tongass Narrows. Enjoy them raw or fried, along with a local craft beer.

Oysters and King crab

Kachemak oysters, grown in floating lantern nets in glacial waters at the tip of the Kenai Peninsula, are plump, firm, and sweet. Order them on the half-shell at Seward oyster bars and restaurants.

Glacier Point oysters are also glacial water fed, cultivated in Halibut Cove, just across Kachemak Bay from Homer. They have a strong, briny, and mineral flavor thanks to the combination of the Gulf of Alaska waters and glacier meltwater. They’re a favorite at the Alaska State Fair.

Sourdough Pancakes

Sourdough pancakes

Sourdough starters made their way to Alaska at the height of the Klondike Gold Rush frenzy. Since commercial yeast was often impossible to come by, gold prospectors turned to a much older method of leavening bread. Some carried sourdough starters with them from California. Others started sourdough cultures in the far north, then passed them down to future generations.

Since every geographic region has its own microflora, sourdough starters are inherently rooted in a place. Whether or not this makes a difference in the final loaf of bread is debatable, but purists often swear they can tell. Some of the sourdough starters used by bakers in Alaska have been going continuously since Gold Rush days. In fact, prospectors were sometimes referred to as “sourdoughs.”

In addition to bread, sourdough pancakes are a distinctly Alaskan favorite. Once griddled up by prospectors over open fires, today, they’re a breakfast staple here. The sourdough starter adds a distinctive tang and a layer of complexity to the pancakes.

Reindeer Meat

Reindeer sausage

Reindeer sausage, found on breakfast menus of many restaurants in Alaska, is a must-try for visitors. The sausage, most of which is made commercially, is lightly spiced with a distinctive meaty flavor similar to link-style pork sausages.

Hot dogs, made with a combination of reindeer meat, beef, and pork, are one of Alaska’s favorite street foods, served at several small stands and food trucks. Split and grilled hot dogs are served on a steamed bun with soda-glazed onions, mustard, and cream cheese. Other toppings include ketchup and relish.

Caribou chili, another Alaska food that uses ground reindeer meat, is made with tomatoes, spices, and a host of canned beans and vegetables for a what’s-on-hand, ever-changing stew that’s always hearty and delicious.

Akutaq

Akutaq Photo by Matyáš Havel on Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Sometimes referred to as “Alaska Native ice cream” or “Eskimo ice cream,” akutaq is often served at Native Alaskan celebrations. In the Inuit-Yupik language, the name simply means “to mix together”. Long ago, this calorically dense Alaskan food was used for sustenance on journeys.

Akutaq was historically made with seal oil, tallow—from reindeer, elk, musk ox, or other animals—fish or dried meat, and berries all whipped together until fluffy. The exact recipe depended a lot on the region of Alaska and the locally available foods. Everything from beaver to candlefish to caribou would have been fair game. Some versions mixed in fresh, clean snow and sweetener, for a frosty treat closer to ice cream.

While Native Alaskans still enjoy akutaq, most modern versions ditch the seal oil and animal fats in favor of commercial shortening. Electric standing mixers also make the once laborious task of beating it all together a breeze. The finished texture is more akin to cake frosting than gelato and is often loaded with local berries.

Wild Berries

Berry pie

Alaska has an abundance of wild berries, which have been an important staple for other Native Alaskan nations for generations. Wild Alaska blueberries, in season August through September, are smaller with a bit more tartness than you may be used to. When they’re incorporated into sweet treats like fruits of the forest pie, cobblers, and ice cream, their superior flavor shines through.

Restaurants offer blueberry desserts in season, and chefs have been known to experiment with sweet and savory combinations like blueberry balsamic sauce. The buffet menu of all-you-can-eat salmon bakes often includes a blueberry dessert to showcase fresh Alaska food.

Salmonberries

Gooseberries, with the same seasonality as blueberries, are used in pies, jellies, and jams sold at local farmers’ markets. Salmonberries are shaped like raspberries, but are bright orange, like salmon roe, hence the name. They’re sweet-sour, but pleasantly so, and are usually eaten fresh or made into preserves.

Nagoonberries

Nagoonberries, also known as Arctic bramble or Arctic raspberries, are a real treat worth seeking out. These sweet, tart berries are known for their juicy texture and make exceptional jams. Interestingly they are highly prized in Sweden, Russia, and even Mongolia, where they also grow wild. They’re particularly important to the Tlingit people. The word “nagoonberries” is derived from the Tlingit name neigóon, which means “jewel.”

Craft Beer

Talkeetna

Alaska’s craft beer scene is alive and thriving, with microbreweries from Ketchikan to Anchorage and beyond. Each has its own special brew styles with seasonal flavors, IPAs, blondes, ambers, and others.

Microbrewery tours are a fun and popular way to get to know different brews and styles of brewing. In Juneau, there’s a bike and brewery tour that takes you on paths around the Mendenhall Glacier, then to Merchant’s Wharf for snacks and a tasting of beers from different breweries in Alaska.

Craft beer in Alaska

Alaskan Brewing Company offers special brews using indigenous ingredients like hand-harvested spruce tips in its Winter Ale, and alder smoke, typical of Alaska smokehouses, to give malt an authentic flavor and allow the beer to age like fine wine.

In Skagway, you’ll find two microbreweries: one with a pub offering beer-focused cuisine like beer cheese soup and beer chili; and the other with taproom tastings, tours, and a store selling merchandise and gifts.

Wine and Spirits

Wine

While Alaska’s climate is not conducive to viticulture per se, there are small enterprising companies creating berry wines, like blueberry and raspberry.

The state has several small distilleries producing vodka, gin, canned gin and tonic, and tonic water products that you’ll find in restaurants, groceries, and specialty shops.

Alajuks

Frybread

Frybread has a long and complicated history among Indigenous communities in North America. It was most likely invented by the Navajo people in the mid-1800s as a means of survival. Forcibly displaced from their ancestral land and food systems, tribes needed to find a way to stave off starvation on meager U.S. government rations. Frybread, made by frying a simple dough of white flour, salt, sugar, and lard, was a means of making something from almost nothing.

Many Native communities have mixed feelings about frybread. For some, this is a traditional food rooted in resilience; for others, a nutritionally poor symbol of oppression. Nevertheless, frybread can be found from the Pueblos of New Mexico to Native Alaskan communities.

Alajuks, or Alaskan frybread, is usually leavened with yeast and enriched with dry milk powder, giving it a slightly cakier texture. It’s often coated in cinnamon-sugar, drizzled with honey, or served with jams made from local berries.

Birch Syrup

Birch syrup

Similar to the process for making maple syrup, birch trees are tapped each season to retrieve sap that’s boiled over open fires to make a concentrated syrup. Birch syrup is thinner than maple syrup with a nutty, more delicate flavor.

Drizzle on pancakes or over ice cream, or use it to sweeten tea, hot or iced. There’s an ice cream shop in Anchorage that uses the syrup to make their special birch-flavored ice cream.

You’ll find birch syrup in specialty shops and some grocery stores.

Black Cod

Black cod

In 1994, chef Nobu Matsuhisa catapulted this particular fish into global stardom at the flagship restaurant of his empire in Manhattan. His miso-glazed black cod, made by curing the fish for three days, was a sensation. Today, black cod, which is also known as sablefish, is highly sought after by chefs all over the globe—and much of it comes from right here in Alaska.

Even diners who claim not to like fish are likely to fall for black cod, which has a clean, delicate flavor profile and buttery texture. It’s delicious in all sorts of preparations and often appears on menus here seared, grilled, or broiled with plenty of butter. Smoked sablefish is also a specialty.

Moose Stew

Moose stew

For a number of Alaskans, hunting a moose is still very much an annual tradition. The state carefully monitors the moose population and limits most hunters to one bull per year. Hundreds of moose are also killed in road accidents each year. Rather than waste perfectly good moose meat, skilled locals often rush to the scene to take care of it.

Given that a fully grown bull can easily reach 1,500 pounds, that often means moose meat for the winter. That’s a real boon, seeing as moose meat is a lot less gamey than a lot of wild meat. It makes for tender steaks, flavorful sausages, and, of course, moose stew. This distinctly Alaskan food is the perfect hearty dish before a long hike.

Pilot Bread

Pilot bread

Hardtack, a kind of biscuit baked until rock-hard and sturdy enough for long voyages, was once a staple throughout much of North America. These days, thanks to other methods of food preservation, it’s largely fallen by the wayside—except in Alaska. Think of pilot bread as hardtack’s tastier, ever-so-slightly more pliable descendant. It was first invented in 1792 by a bakery in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

For many Alaskans, pilot bread is a nostalgic staple. You’ll find it in school lunch boxes as well as crammed into food rations for dog sled racers on the Iditarod. It’s on the bland side by itself, but makes for an excellent foil for everything from berry jam to smoked fish.

Read: Best Things to Do in Alaska

FAQs

Is Alaska a good food destination?

Dome train in Alaska

In general, travelers are much more likely to come to Alaska for its spectacular nature and abundant wildlife than the local cuisine. That being said, Alaska is still a great place to dine and drink. Alaskans tend to be an unpretentious bunch, which means fine dining is rarely the move here. Seek out cozy, local spots serving terrific local seafood and you’ll eat very well.

What food is Alaska famous for?

Tracy’s Crab Shack, Juneau

Alaska produces some of the finest seafood in the world. When you’re wondering what to eat in Alaska, wild salmon, black cod, halibut, oysters, or king crab will all taste delicious and there’s simply no better place to try seafood like this than at the source. The fishing industry here is also one of the most sustainable and ethical on the planet. These fishermen earn a solid living wage and care about protecting their oceans.

What time does dinner typically start in Alaska?

Restaurant in Alaska

Alaskans tend to eat on the earlier side, although this is hardly a set rule. In general, dinnertime is around 6 p.m., although plenty of diners opt for earlier around 5 p.m. Part of this has to do with the fact that most visitors are here for whale-watching, hiking, and other day excursions that require an early start. Many restaurants close by 9 p.m. or even earlier, especially outside of larger cities like Anchorage or Juneau.

Are there any food customs I should know about?

Alaskan salmon bake

Dining in Alaska tends to be a fairly informal affair. Dress codes in restaurants are almost nonexistent. If you bring an open mind about dishes you’ve never tried—say, reindeer sausage—and a hearty appetite, you’ll have a wonderful time.

Note that prices at even casual restaurants may be a bit higher than you’re used to in other parts of the United States. That’s just because almost everything has to be imported from the lower 48 states and Canada. Take the slight upcharge in stride and be sure to tip 20 percent, as restaurant workers here typically have to make all of their money in the warmer months.

Talkeetna

Experience authentic Alaskan cuisine and more on a cruise vacation with Celebrity. When you cruise to Alaska, you’ll experience delectable cuisine both on board and in port.